Resolution Mechanics- How I learned to love the curve

Hello again, dear reader.

This post is taking me a lot longer than I anticipated to write. Despite having a lot of feelings on this topic, it turns out I needed to do a lot of research into it to actually feel comfortable expressing them.

Common Mechanics

My first "minis" game was Dungeons and Dragons 3.5, which uses a d20 system. A task has a target number - armor class or skill check, a character has bonuses, roll a d20 and compare, trying to beat the target number. This is a pretty simplistic look into this mechanic, but at lower levels it's a fairly simple system. Most characters will make one attack a turn, hit or miss, and move on. The odds of any one number is the same as every other number - 5%. A +1 bonus increases your odds of success by 5%. It's a straight forward linear relationship between target number and probability of a success.

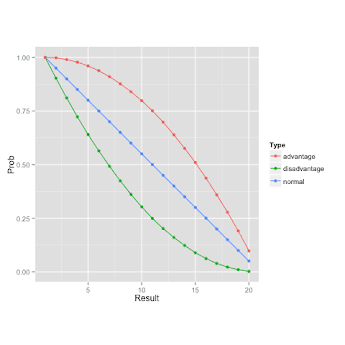

5th edition of Dungeons and Dragons added in the advantage/disadvantage mechanic, which changed things up a little bit. Here, you roll two dice and select the highest (advantage) or lowest (disadvantage) between the two. Taking the higher of two dice increases your average result, but it also greatly reduces the odds of failure on the low end of targets (more on this later).

Since we're talking minis games, we've gotta discuss Warhammer. Warhammer (40k/AoS/Fantasy) uses a d6 vs target number resolution mechanic. Generally what matters is number of successes, since many things have multiple wounds or multiple models per unit, and you're generally rolling somewhere between one and one bucket of dice. Also, there are generally multiple steps - to hit, to wound, armor save (Feel no Pain, damage roll). A single die needing to meet a target number is a fairly flat probability curve, but the combination of multiple stages and potentially many attacks (plus the incredibly common reroll 1s) actually creates a fairly nice curve.

Number of successes out of 1,000 attacks (3+ to hit, 3+ to wound, 3+ save)

Now, I went into this thinking that all of these steps were fairly necessary to generating the probability distribution, but then I played with it a bit.

Top: 3,000 attacks (3+ to hit, 3+ to wound, 3+ save)

Bottom: 1,000 attacks (3+ to succeed)

As it turns out, the peak is in the same place, there's just a slight shift in the standard deviation. All of these steps serve a few purposes. Firstly they obfuscate the probability of success. That is, if you add enough steps in the chain the average player will have a harder time making determinations based on the probability. I've talked about this with people a few times, and this might be what makes it appealing as a casual game. Secondly, the number of steps gives you a ton of places to modify things. Reroll wounds, reroll to hit, AP modifying the save... I think the intent here is to create granularity, but playing with numbers I honestly don't know that I think it does much in practice - but it feels like it does.

The first minis game I played seriously was Warmachine. For those unfamiliar with it, Warmachine forgoes buckets of dice in favor of a 2d6 mechanic to generate probability curves. To hit vs defense, damage vs armor. There are also ways to modify the number of dice you roll, usually to 3d6 but sometimes 4d6, 3d6 drop lowest/highest etc.

The general idea behind this kind of curve is that you're generally pretty likely to succeed at low values, and the median is also decently likely (7 or better on 2d6 is about a 60% chance). Compare to a d20 roll, where the odds of rolling an 11 or better is 50%. You can also see that when lowering your target number the impact can be much bigger than a flat 5% you get with d20s.

The closer you are to the center the larger the probability changes with each step. If you need a 9, adding a +1 to make that an 8 gives you a 14% increase. This rewards being able to eek out increases, but includes diminishing returns. I think, in general, this system is a bit funner for math geeks. It's fairly straight forward once you peek under the hood, but rewards you greatly once you do. Conversely I think this tends to frustrate casual players who don't care much about the underlying probabilities.

I could sit down and write an article about any of the above mechanical systems, and I might at some point, but for now I'm going to keep things fairly limited. These are all grossly oversimplified views of the above systems - doesn't include damage, saving throws in D&D... That is to say, I've simplified the above greatly, so don't get mad at me for how much I'm going to leave out on this next section if it happens to include your favorite system.

Opposed rolls. I feel like these have become something of the new hotness. I first encountered the idea in X-Wing where you roll your attack dice, your target rolls defense dice, and successes cancel. Infinity does something similar with d20s, except a high result cancels all lower results. And I think the best implementation I've seen of it is Marvel Crisis Protocol. Infinity does add a damage roll afterwards, but elsewhere you end up with a resolution mechanic that works out in a single step - something I find incredibly valuable. Further, both players are involved which means on your opponent's turn you aren't just waiting for them to kill your stuff. You also a few ways to manipulate things - canceling dice, rerolling dice, both yours or your opponents, modifying number of dice. There isn't a lack of granularity here, and for me there's something satisfying in a resolution mechanic that resolves things instead of needing extra steps.

And finally, other stuff. Malifaux uses a deck of cards (flip the top card, add your stat) in an opposed roll setup. MonPoc uses strike dice where you're looking for a number of successes based on your opponent's defense. Rock Paper Scissors uses spirits from beyond to move your fingers into different patterns, etc.

I'm sure after reading through this you have some thoughts on which of the above I prefer, but I honestly don't personally know which I think is best. They all seem to have different uses and advantages. Do you have a preference? Post your rant/screed/manifesto in the comments! (I don't know if this thing has a comments section).

*People are bad at math. People are really bad at statistics. There's a fairly famous example in the game Fire Emblem, where the game actually lies to you so the numbers "seem" right to players. It's pretty nifty, for example if you have a 90% chance to hit, the game will actually tell you you have a 78% (https://mobile.twitter.com/MammonMachine/status/1321506096377253889). We tend to have really bad confirmation biases, where if something fails we remember it more vividly than when we succeed. I think the trick is to make these things feel right to players, rather than actually balancing success rates via the underlying probabilities.

Comments

Post a Comment